A linguistic perspective: The harmful effects of responding 'All lives matter' to 'Black lives matter'

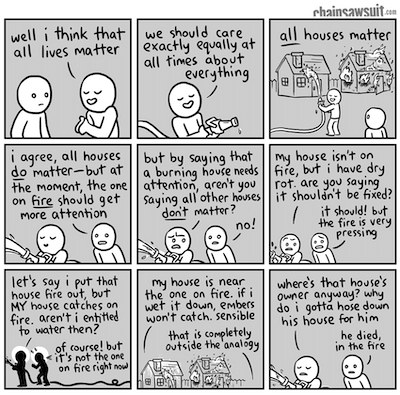

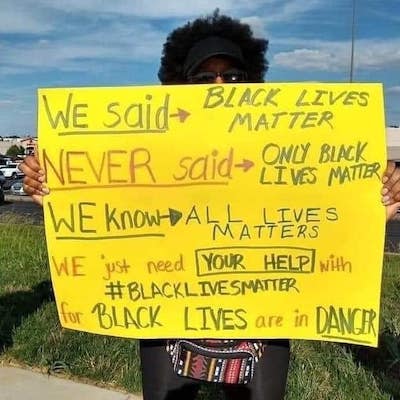

Judith Degen, Daisy Leigh, Brandon Waldon, Zion MengeshaIn this blog post, we provide a linguistic perspective on a response that is often given to the statement “Black lives matter”. We’ll discuss why “All lives matter” is a hurtful, dismissive, and cruel response to “Black lives matter” — even if the person who says it doesn’t intend that effect, and even though we all probably agree that all lives matter. We’re not saying anything here that hasn’t already been expressed in poignant memes, signs, and songs, some of which you’ll find interspersed in this post. We just provide a linguist’s perspective.1

The phrase “Black lives matter” first rose to prominence in 2013. This was the year that George Zimmerman was acquitted in the murder of Trayvon Martin, a black teenager who was walking home when Zimmerman shot him in 2012. The outrage over Zimmerman’s acquittal spurred the Black Lives Matter movement, a now well-known international activist movement that campaigns against violence and systemic racism toward Black people. The movement’s rallying cry, “Black lives matter,” expresses both the belief that Black lives should matter as much as other lives and the frustration that Black lives in fact currently are treated as less worthy. The phrase functions as a call to action to address institutional racism. It has been met both with increasingly widespread support, but also with the response we analyze here: “All lives matter.” So, what’s the problem with this response?

Let’s start with pizza. Say your friend is putting in an order, and asks what you want. You say “I want pepperoni”. Your friend replies: “So, do you mean you want pepperoni, pizza sauce, and cheese?”. Of course that’s what you mean. It’s obvious that you want the pizza sauce and cheese, because otherwise it wouldn’t be a pizza. You didn’t think you had to say it: you assumed it was in what linguists call common ground — information that’s shared between speakers, and doesn’t need to be made explicit. Forcing you to spell out the exact ingredients of your pizza order seems pedantic, and beside the point.

How is this relevant to whose life matters? Put simply, we already know that lives, in a general sense, matter — it’s why we build hospitals and get upset if someone gets sick. Lives are pizza sauce and cheese. But sometimes, circumstances raise a particular question — something as benign as whether you want pepperoni on your pizza, or something more significant. The current question, given all that society at large has shown us — the massive incarceration, police brutality, and wealth inequalities across racial divides, is: do Black lives actually matter? The reaffirmation that Black lives matter is an answer to this particular question.

These kinds of particular questions are what linguists call the Question Under Discussion, or QUD. Whenever we’re talking to someone, there’s a conversational goal we’re trying to achieve, a QUD we’re trying to answer. QUDs aren’t the same as questions we ask overtly. For example, in the pizza case, the question “What do you want?” is an overt question, it’s what your friend actually said. But with your response, you’re addressing the QUD that’s contextually raised by both the overt question and by what’s in common ground with your friend (and possibly other factors). There are two obvious QUDs that your response could be an answer to, shown in the first column of the table. We’ll always italicize QUDs, to show that they’re different from questions.

| QUDs | Interesting states of the world | Alternative to “I want pepperoni” | Interpretation of “I want pepperoni” |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you want pepperoni on your pizza? | want pepperoni / don’t want pepperoni |

“I don’t want pepperoni.” | I want pepperoni on my pizza (in addition to anything else that can be assumed to be in common ground, like pizza sauce and cheese). |

| What do you want on your pizza? | want only pepperoni (no pizza sauce or cheese) / want pepperoni, pizza sauce, and cheese |

“I want pepperoni, pizza sauce, and cheese.” | I want only pepperoni on my pizza, and nothing else. |

As the table shows, different QUDs correspond to different states of the world that we might be interested in. The first QUD distinguishes between two world states: whether you want pepperoni on your pizza, or not. The second QUD corresponds to a different set of world states: whether you want pizza sauce, or cheese, or pepperoni, or some combination of the three. We can tell this is the case by thinking about the utterance alternatives — the other things that a speaker might have plausibly said in a given situation. Whenever we interpret something someone says, we think about the other things they could have said instead. Different contexts — different world states, and different QUDS — will make some alternatives more obvious than others.

For the first QUD, an alternative to saying “I want pepperoni” is, predictably, “I don’t want pepperoni” — it doesn’t say anything about pizza sauce and cheese. You assume your friend will fill that information in based on what’s in common ground. But for the second QUD, an alternative to “I want pepperoni” is “I want pepperoni, pizza sauce, and cheese”. If the question “What do you want on your pizza” is really asking for an exhaustive list of every ingredient you’d like to see on your pizza, then your friend may think that by just responding with “pepperoni”, you don’t want all that other good stuff, because otherwise you would have said it. Linguists call this a Quantity inference or an exhaustivity inference. This kind of inference is based on an expectation that people generally try to be cooperative in conversation, and give as much information as necessary to resolve the QUD.

So does something like a pizza order relate to the much more significant issue of lives mattering? When people say “Black lives matter”, they are addressing the QUD Do Black lives matter? They aren’t saying anything about non-Black lives. People who respond with “All lives matter” are (intentionally or unintentionally) interpreting “Black lives matter” as a response to the Which lives matter? QUD, and therefore wrongly interpret it as “Only Black lives matter.”

As before, we can see how these two QUDs correspond to different world states, alternative utterances, and interpretations:

| QUDs | Interesting states of the world | Alternative to “Black lives matter” | Interpretation of “Black lives matter” |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do Black lives matter? | Black lives matter / Black lives don’t matter |

“Black lives don’t matter.” | Black lives matter (in addition to non-Black lives, which can be assumed to be in common ground). |

| Which lives matter? | Only Black lives matter / Black lives and non-Black lives matter |

“All lives matter.” | Only Black lives matter. |

In response to this explanation, some have suggested that the problem is the ambiguity about which QUD is being addressed, and that it’s up to Black people to clarify this ambiguity, by instead saying “Black lives do matter” or “Black lives matter, too”. We agree with the first part of this and strongly disagree with the second part. We’ll spend the rest of this post saying why.

The QUD is something we infer implicitly, rather than an overt question that is asked explicitly. For instance, if I ask “Do you have any kids?”, the overt question can be answered by simply saying “Yes” or “No”. But people routinely go beyond that, and reply with a more informative answer like “Yeah, I have 2 awesome girls”. Based on common ground, and past interactions where people talk about kids, they’ve inferred that the intended QUD isn’t just Do you have any kids? but How many kids do you have, and what are they like? Your “Yeah, I have 2 awesome girls” response is cooperative: you recognize that I wasn’t being as explicit as I could have been, because it might have seemed impolite or long-winded to ask the longer, more explicit question. In answering cooperatively, you recognize and reinforce my intended QUD.

An alternative, less cooperative response forces a change in the originally intended QUD. If you simply respond “Yes”, you’re shifting the QUD to Do you have any kids?, which is weaker than the intended QUD (in that its answer provides less information) and therefore will probably make you seem rude or aloof. We infer QUDs all the time in everyday conversation, without even thinking about it. Likewise, we notice and keep track of these reinforcements or changes to the QUD as they happen.

The gist of the problem with responding “All lives matter”, then, is the following: the response “All lives matter” forcefully shifts the intended QUD Do Black lives matter? to __Which lives matter?__ — a QUD that’s as irrelevant as the question of whether you want pizza sauce and cheese on your pizza. Ordering pizza is low-stakes: you might call your friend a pedant and tell them to get on with it. Shifting the QUD to Which lives matter? is violent. It denies the relevance of the intended “Do Black lives matter?” QUD, which is itself the result of the historical and current institutional violence and systemic racism against Black people. By denying the relevance of the Do Black lives matter? QUD, “All lives matter” also denies the history of hurt, dismissal, and oppression that makes the Do Black lives matter? QUD salient in the first place. That is why the response is so insidious: it is a statement that we should generally agree with, yet in response to “Black lives matter” it ends up denying a history of violence against Black people.

This point is also succinctly captured in the 2017 Body Count song “No Lives Matter”. They say:

When I say ‘Black Lives Matter’ and you say ‘All Lives Matter’ […]

You’re diluting what I’m saying

You’re diluting the issue

The issue isn’t about everybody, it’s about Black lives, at the moment

So, if you still find yourself wanting to respond “All lives matter”, “White lives matter”, or “Blue lives matter”, ask yourself why Which lives matter? is a more important QUD to you than Do Black lives matter? — keeping in mind that the idea that lives matter in general is firmly within our collective common ground. If it’s that you don’t believe the premise that Black people are treated worse in America than non-Black people, we have listed some resources below that contain ample evidence to this effect.

Notes

1 One might argue that “Black lives matter” and “All lives matter” are no longer transparent utterances, with transparent meanings, that can be analyzed according to rules and practices of everyday conversation. Rather, they could be seen as similar to sports team chants — where the act of saying them identifies you as belonging to a particular group — or, in the case of “All lives matter”, dogwhistles — coded messages that are intended for a particular audience, to communicate a particular set of beliefs. We don’t disagree but nevertheless find it useful to give an account of the literal meanings of these phrases, and their communicative effects.

Edit, Aug 30, 2021: This year, Philosophy professor Jessica Keiser published an academic article that lays out the ideas in this post in a lot more detail. Check it out if you want to get into the nitty-gritty!

Additional resources

If you find yourself confused or attacked by the notion that Black people are treated worse by society than white people, or would simply like to inform yourself further, here are some of the many resources that document the situation:

- Watch Ava DuVernay’s documentary 13th or read Michelle Alexander’s book (new 2020 edition) The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness to see how the oppression of Black people is perpetuated via the prison-industrial complex and racist policies that continue to reinforce segregation.

- Jennifer Eberhardt’s 2019 book Biased – Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice That Shapes What We See, Think, and Do provides an overview of the research on cognitive biases and stereotypes, especially racial bias in criminal justice.

- The 2020 paper by Steven O. Roberts and Michael T. Rizzo, The Psychology of American Racism, contains many references documenting the current state of American racism. Some excerpted facts:

White students are perceived as more compliant than students of color, which decreases their likelihood of being expelled (Okonofua et al., 2016).

White homeowners are perceived as cleaner and more responsible than homeowners of color, which increases their home equity (Bonam et al., 2016)

White criminals are perceived as less blameworthy than criminals of color, which decreases their likelihood of being executed (Baldus et al., 1998; Scott et al., 2017)

The practice of redlining has systematically denied communities of color access to real estate and set the precedent for a range of federal and state policies that continue to disadvantage communities of color today (Rothstein, 2017)

In 2018, 97% of CEOs at Fortune 500 Companies were White (Fortune, 2018), as were 98% of past U.S. Presidents. This hierarchy, rooted in American history and perpetuated by racist ideologies, practices, and policies (e.g., Plessy v. Ferguson, Brown v. Board of Education) rather than an inherent superiority of White Americans (Alexander, 2010; Bonilla-Silva, 1999; Williams, 1987), plays a critical role in the psychology of American racism, such that several cognitive biases and social ideologies reinforce the conception of White Americans as superior.

The status of “American” itself is readily granted to White Americans, and often denied to Americans of color, and particularly Asian and Latinx Americans (Harris et al., 2020; Zhou & Cheryan, 2017)

Because White Americans have historically and contemporarily constituted a numerical majority, and occupied most positions of power, they have been able to establish societal norms (e.g., which accents are considered standard and who is allowed to participate in political elections), achieve goals (e.g., who is advantaged on “standardized” English tests and allowed to ascend to political positions of power), give orders (e.g., how English should be taught and which legislation to pass to mandate those teachings), control resources (e.g., establish educational institutions that shape curricula and financial institutions that shape economies), and dominate and exploit others (e.g., socialize racial minorities toward an “American” way of thinking, build hazardous-waste landfills that disproportionately affect communities of color; see Alexander, 2010; Baugh, 2000; Bullard, 2000; Duran & Duran, 1995)

Dixon and Linz (2000) compared how often people were depicted as criminals and victims on television to actual crime reports and found that Black Americans were overrepresented as criminals and underrepresented as victims, whereas White Americans were underrepresented as criminals and overrepresented as victims. Viewers exposed to such portrayals are more likely to perceive Black people as criminal, report anti-Black attitudes, and support harsher criminal sentencing against Black people (Dixon, 2008; Tukachinsky et al., 2015).

Weisbuch, Pauker, and Ambady (2009) examined 11 popular U.S. televisions shows, each with an average weekly audience of 9 million viewers. Characters showed more negative affect and body language toward Black characters than toward White characters of the same status, which increased participants’ anti-Black attitudes.

References

-

Baldus, C., Woodworth, G., Zuckerman, D., Weinder N. A., & Broffit, B. (1998). Racial discrimination and the death penalty in the post-Furman era: An empirical and legal overview, with recent findings from Philadelphia. Cornell Law Review, 83, 1638-1770.

-

Baugh, J. (2000). Linguistic Profiling. New York: Routledge Publishing.

-

Bonam, C. M., Bergsieker, H. B., & Eberhardt, J. L., (2016) Polluting black space. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145, 1561-1582.

-

Bonilla-Silva, E. (1999). The essential social fact of race. American Sociological Review, 64, 899-906.

-

Bullard, R. D. (2000). Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality (3rd Edition). New York: Routledge.

-

Dixon, T. L. (2008). Network news and racial beliefs: Exploring the connection between national television news exposure and stereotypical perceptions of African Americans. Journal of Communication, 58, 321-337.

-

Dixon, T. L., & Linz, D. (2000). Overrepresentation and underrepresentation of African Americans and Latinos as lawbreakers on television news. Journal of Communication, 50, 131-154.

-

Duran, E., & Duran, B. (1005). Native American postcolonial psychology. Albany: State University of New York Press.

-

Harris, K., Armenta, A. D., Reyna, C., & Zárate, M. A. (2020). Latinx Stereotypes: Myths and Realities in the Twenty-First Century. In J.T. Nadler & E.C. Voyles (Eds.) Stereotypes: The Incidence and Impacts of Bias (pp. 128 – 143). Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

-

Okonofua, J. A., Walton, G. M., & Eberhardt, J. L. (2016). A vicious cycle: A social- psychological account of extreme racial disparities in school discipline. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11, 381-398.

-

Rothstein, R. (2017). The Color of Law. New York: Liverlight Publishing.

-

Scott, K., Ma, D. S., Sadler, M. S., & Correll, J. (2017). A social scientific approach toward understanding racial disparities in police shooting: Data from the Department of Justice (1980–2000). Journal of Social Issues, 73, 701-722.

-

Tukachinsky, R., Mastro, D., & Yarchi, M. (2015). Documenting portrayals of race/ethnicity on primetime television over a 20-year span and their association with national-level racial/ethnic attitudes. Journal of Social Issues, 71, 17-38.

-

Weisbuch, M., Pauker, K., & Ambady, N. (2009). The subtle transmission of race bias via televised nonverbal behavior. Science, 326, 1711-1714.

-

Williams, C. (1987). The destruction of black civilization: Great issues of a race from 4500 BC to 2000 AD. Chicago, IL: Third World Press.

-

Zhou, L. X., & Cheryan, S. (2017). Two axes of subordination: A new model of racial position. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112, 696-717.